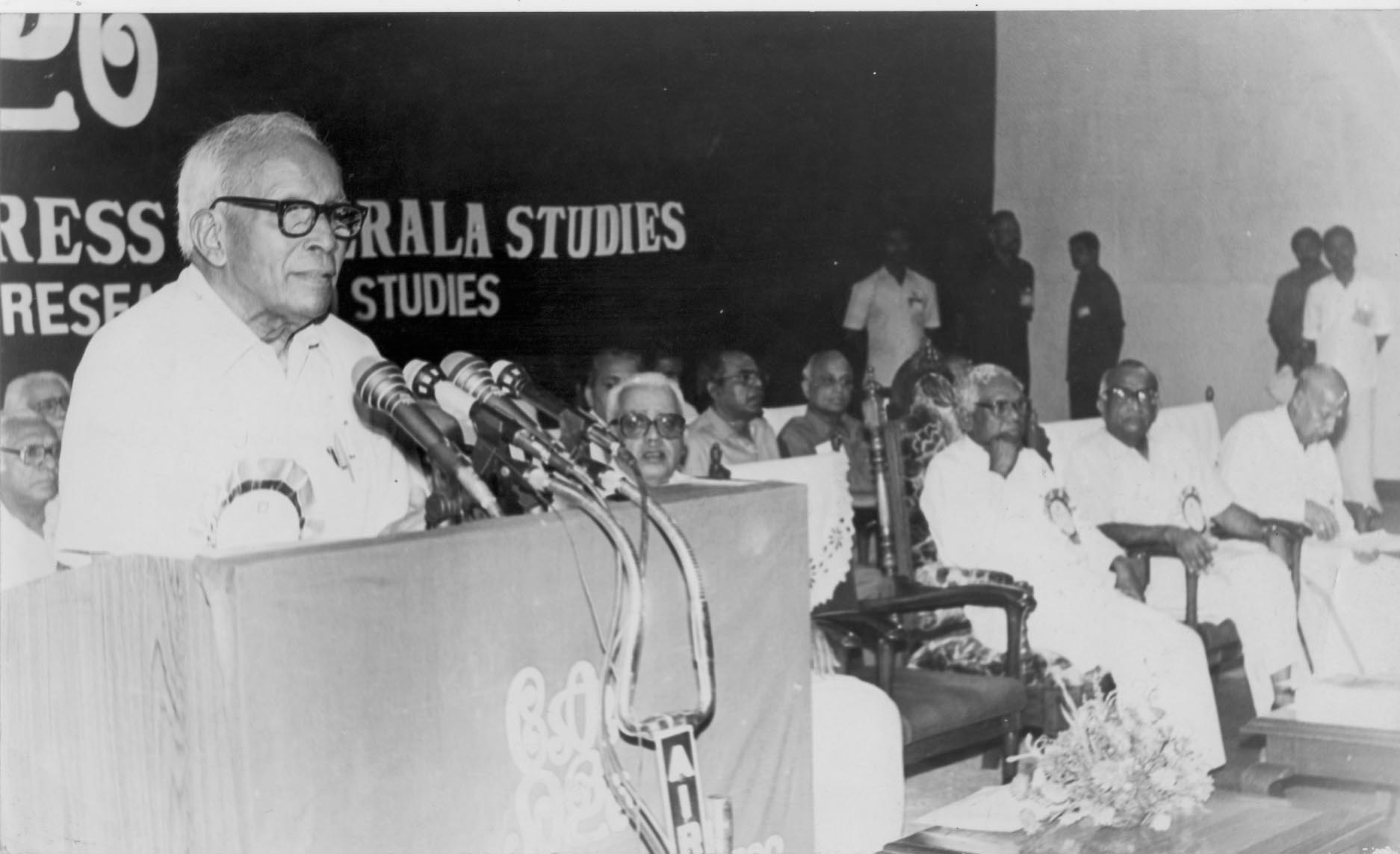

Presidential Address by E.M.S. Namboodiripad at International Congress on Kerala Studies, 1994

Respected Vice President, distinguished guests from abroad, scholars and socio-political activists from all over Kerala and India: I thank you all for having accepted our invitation to participate in this Congress of scholars in various disciplines and of socio-political activists.

This is a unique event. Gathered here are over a thousand distinguished persons who, in 73 sessions and over three days, will discuss various aspects of the sociology, economy, politics, culture and natural resources of Kerala. Laypersons will profit from the presentations of scholars, while scholars will benefit from the practical experience of socio-political activists. Such an exchange will be of great help to us in Kerala, since it will provide a new perspective on our socio-cultural, economic and political life.

This is not a seminar that is expected to come to precise conclusions on how the various problems of Kerala are to be solved. That is a task that political parties and social organisations in Kerala shall have to undertake on the basis of their experience, including the experience they gain at this Congress.

As for the A.K.G. Centre for Research and Studies, I want to assure you that we will do our best to continue the dialogue between scholars and activists that will take place at this Congress. The A.K.G. Centre for Research and Studies was founded in honour of the great revolutionary A.K. Gopalan. For many years, A.K. Gopalan was the President of the All-India Kisan Sabha, travelling all over the country, organising rural and urban toilers to fight oppression and exploitation. From the first general election in 1952, and for more than two decades, A.K. Gopalan was the leader of the Communist group in the Lok Sabha (for almost the entire period, the Communists formed the largest opposition group in the Lok Sabha).

Though no academic scholar himself, at the end of his life he expressed a wish to start a school for activists from all walks of life. When he died, we thought it appropriate that an "unofficial University" be established to perpetuate his memory, an institution at which academic scholars and socio-political activists could exchange information and experience. I had the privilege of working with A.K. Gopalan for almost the entire period of his political activity, and was chosen to head this organisation, and it is as the Director of the Centre that I shall raise a few practical problems faced by us in Kerala.

Although called an "unofficial University", the founders of this Centre, including myself, have no claim to academic scholarship. It is, however, our good fortune that, in the course of our work, many distinguished scholars in various disciplines have associated themselves with the work of this Centre. We are socio-political activists and our friends from academics have found it profitable to interact with us.

This Congress is, of course, a far bigger event than ever before. Let me thank you once again for having come and having agreed to give us the benefit of your experience, knowledge and wisdom. The Centre is named after the most eminent Communist of Kerala, and bears the impress of the Communist movement in the state. The birth and growth of the Communist movement in India and in Kerala and the problems of the movement are the concerns of the Centre.

I consider it appropriate to use this occasion to mention some of the contributions that we as a Party have made to academic thinking and scholarship. "Philosophers have in various ways interpreted the world, the point is to change it" — so reads Karl Marx's thesis on Feuerbach. We Communists of Kerala and of India have not confined ourselves to political activism, and are proud of having made contributions to academic thinking as well.

The Socialist-Communist movement began in Kerala in the mid-1930s, more than a decade after it began in India. In those early years of the movement some major socio-economic, political and cultural problems confronted us, and our work in respect of these problems was the basis of our initial contribution to the development of scholarly and academic thought.

The first of these problems was the existence of feudalism that had a peculiarly Kerala character. I have called Kerala feudalism the combined domination of the feudal landlords (in the economic sphere), the Brahman-dominated upper castes (in social life) and the rule of the princes and chieftains of the different component parts of Kerala. The combination of these three forms of domination and the strength of the people against them were the essential elements of socio-economic life in Kerala.

Our struggle against the British rulers for national freedom was, consequently, integrated with the movement against landlordism, upper-caste domination and princely rule. In 1934, when we formed the Congress Socialist Party in Kerala, we considered this task of integrating the movement for national freedom with the struggle against landlordism, upper-caste domination and princely rule to be the basic task of our movement. We achieved this integration through many-sided political activity.

First, we believed that, after freedom from British rule was attained, the territory of the princely states of Travancore and Cochin, and the Malabar district of Madras Presidency in British India had to be brought together into a united Kerala. While a united Kerala was our ultimate objective, we thought it immediately necessary to work for democracy in the princely states. The struggle for responsible government in Travancore established unity among radical democrats and Communists all over the state, and this unity helped our struggle succeed.

Secondly, we concerned ourselves with the problem of the economic domination of the feudal landlords (janmi). The janmi system dominated agrarian relations in Malabar, and existed in many parts of Cochin and in some parts of Travancore as well. Militant trade union movements in Travancore, Cochin and Malabar, and the militant peasant movement in Malabar were very important features of the radical democratic and freedom movements in Kerala in the 1930s.

As a result of the activities of these mass organisations, and of the local units of the Kerala Pradesh Congress Committee in Malabar, the Cochin Congress and Prajamandalam in Cochin, and the State Congress of Travancore, socialism and communism became forces to reckon with in Kerala. We built the Kisan Sabha and raised the issue of ending feudal landlordism free of cost to the rural toilers.

This demand was articulated in the dissenting note of three left-wing Congress Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) who were members of the Malabar Tenancy Inquiry Committee which submitted its report early in 1940. To strike a personal note, I was one of the three MLAs, and my note of dissent presented the theoretical argument for ending feudal landlordism and distributing land to the rural toilers free of cost. Although it was written as a matter of practical revolutionary work, that dissenting note of mine had some academic value.

The demand and the document became the basis on which the Kisan Sabha developed in the 1940s. Our agrarian demands culminated in the enactment of an agrarian legislation by the first Communist government of united Kerala (1957-59). The legislation came into force in 1969. The struggle waged from the 1930s onwards and the legislative activities of the first Communist and the United Front governments together thus brought about a revolutionary change in agrarian relations, perhaps the best possible within the framework of the bourgeois Constitution of India.

Next, the movement was confronted by the problems of the oppressed castes in Hindu society, and of the underprivileged religious minorities, Muslims and Christians. We based our activity on the theory of class struggle, rather than the ideologies of castes and religious communities. We try to bring together toiling people of all castes and religious communities in organisations of industrial and agricultural workers, toiling peasants and all other sections of the working people.

In this process, we were up against the Indian National Congress and other bourgeois parties of liberal democracy, and against caste and communal organisations that had no use for class struggle. While the leaders of caste and religious communities spent their energies in building caste and communal organisations, we built class organisations of the working people in which toilers of all castes and religious communities came together. The Alleppey general strike in Travancore and the north Malabar struggles of peasants in the 1930s were our answer to the leaders of caste and communal organisations.

Another question that we dealt with when we formed the Socialist-Communist movement in the 1930s was that of the role of art and literature in revolutionary social change. We were deeply influenced by the call of Maxim Gorky and other giants of international proletarian literature and of Indian writers such as Munshi Premchand to base literature on the lives and struggles of working people.

We founded the first organisation of progressive writers in Malayalam in 1937. When it began, the organisation was mostly confined to revolutionary political activists who dabbled in literary activities as well; it was broadened in the 1940s to include established writers and critics who were committed to revolutionary practice. There were subsequent conflicts between the two groups of progressive writers and bitter polemics between the Communists and the rest in the progressive writers' movement. This clash of ideas led to a clarification of issues on the form and content of writing.

This discussion on literature and progressive literature also helped the growth of new trends in other areas of artistic and cultural activity, for instance, drama, cinema and the visual and performing arts. That was how the present organisation of progressive writers and artists came into being. It is an organisation that draws on the best in the arts and cultural activities for the people's struggle for democracy and secularism.

Some of Kerala's most celebrated writers, poets, musicians, cinema artists and specialists in the visual and performing arts are active today in the movement and are participants in this Congress. I am sure that their presence here will help the Congress to come to a more clear understanding of the problems of art and literature in Kerala, and that they will benefit from the exchanges here.

One of the important contributions of the Communists during this period was the elaboration of the doctrine of the multi-national character of united India. We advanced the theory that every people who have their own language and distinct culture (such as the Malayalam-speaking people of Kerala) are distinct nationalities. These nationalities were united in the struggle against British imperialism, a unity that was to be carried forward in the post-Independence period in a united federal India.

The objectives set by the Party were those of unity in diversity, and a united India with as much autonomy as possible for the new linguistic states. Though the detailed formulation of the concept was not faultless, the main idea was fully correct. This was a distinct contribution made by the central leadership of the Communist Party of India to Indian politics.

This doctrine of the multi-national character of united India was taken over and elaborated by the Kerala Communists. In a pamphlet I wrote in 1945, I put forward the idea that Malayalees in Malabar, Cochin and Travancore be united in a single, unified state of Kerala. The southern Tamil-majority parts of Travancore and the Kannada-majority parts of north Malabar would, of course, go to the linguistic states of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. This was the central idea of the pamphlet titled "A Crore and a Quarter Malayalees".

That attempt to apply the idea put forward by the Central Committee of the Party to the conditions of Kerala was accompanied by two similar attempts by P. Sundarayya in Andhra and Bhowani Sen in Bengal. Such was the conceptual framework of nationalities and a united India that led the revolutionary movement to the Punnapra-Vayalar upsurge in Travancore, the Telangana struggle in Andhra and the Tebhaga movement in Bengal. These revolutionary movements and the idea that Kerala, Andhra and Bengal were the homes of distinct nationalities, marked the Communist Party off from the Congress and other bourgeois parties.

This perspective of a free India with national unity at the centre and with the widest possible autonomy for linguistic states was a new and revolutionary perspective. The concept of different nationalities in a united India was opposed to the Congress idea of a centralised and unified India with no state autonomy and to the Muslim League's doctrine that Hindus and Muslims were different nationalities.

The emergence of this concept of nationalities influenced our Party's effort to study society and history in Kerala. I personally made a humble contribution to this effort by writing the first history of Kerala that was based on the Marxist theory of class struggle. The attempt did, of course, have its weaknesses, since the history of society in ancient Kerala was steeped in mystery. I however succeeded in bringing out the fact that, since at least the mediaeval period, what I called "caste-janmi-prince-chieftain-domination" (the peculiarly Kerala form of Indian feudalism) was well established in Kerala.

Although I had subsequently to revise and correct the concept with respect to the history of ancient Kerala, what I wrote regarding the mediaeval and modern periods has stood the test of time. Many persons are present at this Congress who have done original research on Kerala and have uncovered many facts about the history of ancient Kerala. I am sure that the studies and research of my friends will deepen our understanding of Kerala history and correct the deficiencies of my assessment of Kerala history.

Our studies of Kerala history and the revolutionary struggle in which we were involved in the 1940s and early 1950s made us foremost among political organisations in our understanding of the socio-economic, political and cultural problems of Kerala, and ahead of others in our attempt to solve these problems. Our study and our practice enabled us to emerge as the major political party in the state in the post-Independence period (the Party also emerged as the major political party in West Bengal and Tripura).

In 1957 the Party emerged victorious in the first parliamentary and legislative assembly elections held in the new state. Ever since, the left has remained the leading force in the politics of Kerala. Looking back, I feel one of our key failures has been in understanding issues connected with religious minorities in Kerala. Unlike West Bengal and Tripura, the population of Kerala has large Christian and Muslim minorities, which form over 40 per cent of the state's population.

Muslims and Christians are under the predominant influence of religion-based leaders, that is, of the Muslim League and the Church. The Muslim League and the Church, for various reasons, took strong anti-communist positions, which hindered the development of Kerala in no small measure. Now the situation is changed. Sections of the clergy and laity are joining hands with Communists in the struggle for national unity, democracy and improvement in the living and working conditions of the common people.

Changes are also taking place in the Muslim community, changes that have opened doors of cooperation between devout Muslims and Communists. In the Hindu community, too, the message of revolutionary humanism preached by Swami Vivekananda in India and by Sree Narayana Guru in Kerala are bound to make more and more sadhus and sants cooperate with Communists. Lenin visualised "cooperation between the believers and Communists in building a heaven on earth rather than speculating on having heaven in the other world"; such cooperation has become possible.

Our theory and our practice have left deep imprints on Kerala society. Land reforms, the growth of various mass organisations of people, the spread of education, improvements in the health status of the people, and so on, have transformed Kerala significantly, and have attracted much scholarly attention. I refer to the much-discussed "Kerala Model of Development". That model has its positive features: the emphasis laid on education, public health, communications, etc., has certainly helped the formation of an independent working class in the state; it has also helped the emergence of the organised movement of various sections of the working people.

These are certainly assets of which I am proud. It should, however, be mentioned that the negative features of contemporary economy and society in Kerala are too serious for us to neglect. The fact of the matter is that, although important advances have been made in respect of what are now called "human development indicators", Kerala faces today an intense economic crisis in the spheres of employment and of material production, agricultural and industrial.

In fact, I am inclined to believe that while we have spent much time and attention on "social-sector" issues of welfare and the improvement of the living standards of the people, we have not paid enough attention or shown adequate concern for pressing problems of economic growth and material production. I make a request: let not the praise that scholars shower on Kerala for its achievements divert attention from the intense economic crisis that we face. We are behind other states of India in respect of economic growth, and a solution to this crisis brooks no delay. We can ignore our backwardness in respect of employment and production only at our own peril.

There are numerous papers that will be presented at this Congress that analyse the various manifestations of the economic backwardness of Kerala, its retarded industrialisation, infrastructural bottlenecks, agricultural stagnation, and mounting unemployment. I am also certain that you will discuss the economic, technological and sociological factors that have contributed to the economic crisis.

The restructuring of global and national economic and political institutions and the new policy regime are undoubtedly going to intensify our problems. The situation calls for political solutions. As a political activist, to resist and defeat these anti-people changes and policies is my first priority. It is going to be a long drawn-out struggle.

I do not subscribe to the view that nothing can be done in our state until these national policies are reversed. I am proud to refer, in this context, to the efforts and achievements of the people and government of West Bengal, which I shall illustrate with the example of agricultural growth in that state. From 1965 to 1980, West Bengal was far behind the rest of India in respect of agricultural growth.

Thanks to the Left Front's achievements in land reform and in democratic decentralisation, and despite the constraints that are imposed on state governments in our system, rural West Bengal is transformed. Rates of agricultural growth in West Bengal after 1983 were the highest among the 17 most populous states of India, and these rates have increased in all districts and for almost all major crops.

Within the limitations imposed by global and national structures, we too will have to find practical solutions to the various problems that our state faces. We cannot let the present situation drift. We have got to reach a consensus as to what measures are to be adopted to accelerate economic growth without sacrificing the welfare gains and the democratic achievements of the past.

I feel that we need to take fresh stock of our present situation and draw up a new agenda. This is not the task of any one political party or of political parties alone. It is a national task, in which the academic community and scientific professionals have an important role to play.

When we set out to draw up an agenda for a democratic Kerala half a century ago there was hardly any academic community and few modern professional experts. We activists took up the challenge, and I have spoken of some of the contributions we made in the process. The problems of today are different and, perhaps, more complex.

We need urgently a dialogue between academics and professionals in various disciplines and political activists, and between various political parties both of the left and the right on how the development process in our state can be sustained through strengthening the material production base. Political differences will remain, but a consensus on a broad platform of measures to overcome the crisis can be achieved.

Our great assets are our mass organisations and the democratic consciousness of our people. The combined strength of all mass organisations in the state is about ten million. Besides, there is a vast network of cooperative organisations and movements, such as the organisations of the library and literacy movements.

I am aware that there are some people who consider all these to be the bane of Kerala society. I have devoted my life to mobilising the people for the radical transformation of our society, and I cannot but disagree with such perceptions. I feel that one big question that we face is whether the organised strength and political consciousness of our people can be used to increase production and productivity.

I want to answer in the affirmative. But there is a precondition: the government and the ruling classes must change their attitude to the organisations of the people and their demands. Instead of suppressing people's struggles and adopting negative attitudes, amicable solutions should be found through collective bargaining and discussions. Further, institutions and social mechanisms have to be developed to ensure that the toilers get their due share from increased production.

I must emphasise the importance of democratic decentralisation in this context. In this respect, I must confess that our progress has been very slow. The 72nd and 73rd constitutional amendments have been utilised for bureaucratic centralisation rather than for democratic decentralisation. We must also establish new social and economic institutions for land and water management, to improve the quality of our social infrastructure and for cultural development. Modern science and technology have to be integrated in the development process in a sustainable way.

All these and other tasks require deep and frank dialogue between everyone who is interested in the progress of the state. This is the context of the first International Congress on Kerala Studies. We of the A.K.G. Centre for Research and Studies are proud to host the Congress and look forward eagerly to hearing your opinions. I hope that the discussions here will help us all in the task of planning for a new Kerala in a new India.